The Funerary Violinist Today

It is not infrequently that people have asked me what is the relevance of funerary violin to them? Other than the obvious send off that it can offer, they seem to see no link between the many issues and burdens that trouble their everyday lives and the Art of Funerary Violin. But they could not be more wrong. If only they would take a few minutes to contemplate the profound lessons that can be learnt from the Art, they would see that the ramifications reach out, way beyond the Chapel of Rest, beyond Art and Culture itself, and into our general relationship with the world, mortality, and how we respond to it. Just as an archaeologist can perceive many elements of a long lost civilisation through a single damaged artefact; or an ecologist can judge the health of an entire ecosystem from a single lichen: just so the thoughtful and far sighted among us can judge the spiritual and material values of our own culture through the status and social depiction of the Funerary Violinist. The current poor health of what was once a great tradition is testament to the declining vision, or, dare I say it, selective wilful blindness, of the society we express through our everyday lives. Certainly the thread of continuity was broken by the Great Funerary Purges, but today, in the light of all that which has been discovered in recent years, and indeed that which is presented herein, it is no longer possible to plead simple ignorance. Despite incredible efforts on the part of the Guild of Funerary Violinists, and others, in recent years, it is apparent that our culture has turned its back on the serious and meaningful, death itself has become taboo, and our hopes for a renaissance of our venerable Art, now long overdue, are to be thwarted by the overwhelming indifference of a media dominated material consumer world.

But we look to the future, and we know that such a state of affairs cannot possibly last, for funerary rites are an eternal feature of Man’s psychological makeup. They are among the oldest known rituals. Even in the days before artefacts (that might give away to the imaginative scholar any number of bold speculations as to the spiritual world of ancient peoples), the earliest of modern humans are known to have sprinkled their dead with red ochre – a natural orangey pigment. This is taken to be among the first signs of the spiritual consciousness that allegedly sets us apart from the animals. Indeed, as we have seen, much of our understanding of history is drawn from the leftovers of complex funerary rituals – such as the Sutton Hoo ship burial; the pyramids of Egypt etc etc. Our knowledge of many early civilisations is limited entirely to what can be gleaned from their grave goods, and the implications therein. Back in the present day we see a bewildering array of funerary rites around the world, from marathon prayer session, to the burning of massive pyres etc. Yet when we look to our own modern Western Culture we see little more than a basic rejection of the notion of Death.

Today we are, as a society, convinced that modern medicine will prolong life to the point where it is no longer worth the effort. Of course this point to a man or woman in their twenties is very different to a person of seventy five, but the reassuring smile of medical science means that only the tragically unfortunate must ever contemplate the reality of death whilst in their prime. Once the body is near to breaking down for good, they are sent away to a nursing home that deals with everything at a distance. Most of us have never seen a dead body. If there is a death in the family it is usually that of an elderly relative that we last saw some time ago. The brief funeral is led by somebody who never met the deceased, and it is not uncommon for mistakes to be made in summarising the life. The body is safely packaged in a standard off-the-shelf coffin and, more often nowadays than not, this coffin puts in only a brief appearance before being mechanically retracted behind curtains. All this to the plaintive strains of a cassette player churning out commercially motivated music. Upon occasion an electric organ is played (badly) by another stranger to the deceased and their family. A week or so later they are presented with an elegant wooden box, or urn, containing the unrecognisable ashes, which are usually sprinkled somewhere pretty. If there is a burial, a simple headstone will suffice, or a small plaque embedded in the ground, but to celebrate the death with a grand mausoleum would be considered tasteless. Of course, there are a number of specialist trades that deal with the dead on our behalf, such as hospital workers, mortuary attendants, undertakers etc. but they are the exception to the rule.

This whole process has evolved over the last eighty or so years to distance us from any uncomfortable notions of our own mortality. In a world where animal products come processed and packaged from the supermarket; where plastic surgery can keep us looking young (though a little strange) well into our seventies; where our apparent gods are celebrated for the enviableness of their lifestyles; it is no great surprise that mortality is placed at the very back of our minds. And in this current state of denial anything that focuses the attention on the reality of our great journey trough life will inevitably be rejected. And that has been the recent fate of the great Art of funerary violin.

If you take a walk through any British nineteenth century cemetery, such as Highgate (London) or Woodvale (Brighton) you will see a wonderful array of gothic sculptures, grand mausolea, and crumbling stones overgrown with bushes and brambles – a remnant from the days when Romantic Gothicism was deemed an appropriate response to death. What more fitting place, you may think, for a funerary violinist to rehearse the tone that is the mark of his trade, but according to Southwark council by-law 3 article 7.2 (among others) you would be wrong. Not only has cultural evolution turned it’s back on the Art of Funerary Violin, but individual councils have enacted specific laws to prevent the prospective funerary violinists from learning his art. Some may consider rehearsing in cemeteries unnecessary but to them I say – could a formula 1 driver practice his skills along winding country lanes? – could a cross channel swimmer train in a local swimming pool? Of course they could, but it would only be useful up to a point. The final element is missing, and without it their training is inevitably limited. Just so with the Funerary Violinist. Performing at a funeral, venerating the dead, becoming a vehicle for the grief of many is not just another concert. It has a quality all of it’s own, and without the proper rehearsal environment this cannot be achieved. Ask yourself – would you like an unrehearsed violinist to play at the funeral of one of your loved ones? I think not!

Let us consider for a minute what a funerary violinist actually does. The key to this is sensitivity. The Chapel of Rest is filled with strangers, all in a highly emotional and sometimes desperate state, the coffin containing their loved one is laid out at the front, and whilst everyone is still stirring the violinist takes up his bow (I say his as traditionally funerary violinists were all male, though the Guild is now hesitantly encouraging membership from woman, albeit Honorary and not Executive) and begins the ritual. This moment is crucial and if misjudged can lead to disaster. In his tone he must first convey the deep grief that is present in the room and then transform it into a thing of beauty. By the time he is finished a deep and plaintive calm should have descended upon the room, and the bereaved should be ready to hear the eulogy. The music must be simple, any hint of flashiness or empty virtuosity, even the slightest breath of ego, will destroy the spell. At the end of the ceremony he must again strike up and take them back to the world of sadness and grief for the weeping at the graveside (or in the car park if the body was cremated). This is music as magic, with the ability to transform the mood and perceptions of the audience in a way far beyond the concert hall – and it only works on such a deep level because the audience is in a heightened emotional state. It is a position of great responsibility and should not be taken lightly. Sadly, it is a profound reflection on our current culture that more often than not the default choice is an electric organ playing something nondescript, or a pre-recorded cassette. I believe this is a response to our fear of the power of meaningful rituals – and, again, our love of plastic packaging.

In many ways the Funerary Violinist is the last bastion of Romanticism. In a world where Art refers to all things so long as they are in an art gallery; where John Cage has demonstrated that all sound in a concert hall is music: the Funerary Violinist remains un-redefined. It is a role that defies reinvention because it deals with an absolute. Death remains death whatever we call it, however much we distance ourselves from it, and just so with Funerary Violin. It is the channel for the expression of death, and as such can only be what it is. To stray too far from the Truth is to fail. In today’s world the Funerary Violinist is the lone Romantic who dares to stand at the peak and look down into the black chasm beyond, whilst everyone else cowers at the bottom admiring designer shoes in shop windows. As a civilised culture we cannot afford to let this ancient and venerable tradition, which dates back over 500 years, remain forgotten; we cannot afford to ignore the many valuable lessons it holds for us; and most of all, we cannot afford to push Death and mortality ever further from our minds, for that way lies only Madness.

extracts:

- Read the Forword

- Read an extract from the Introduction

- Read Charles Sudbury's account of a Funerary Duel

- Read Wilhelm Kleinbach - the Last of the Practicing Funerary Violin

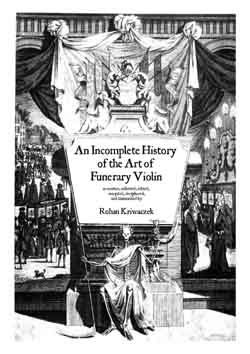

To purchase a copy signed by Rohan Kriwaczek, author and Acting President of the Guild of Funerary Violinists, and stamped with the official Guild of Funerary Violinists stamp for only £24, plus £1 postage worldwide, click below

|