an extract from Charles Sudbury - England's Dark Genius of Funerary Violin

The other violin performance that was to have an influence upon Sudbury was not a concert, but a funerary recital, or rather duel, between Pierre Dubuisson and Jean-Paul Couret, for the interment of Georges Couthon, a notable Parisian wine merchant, at the cemetery of Père-Lachaise. In the years following the Revolution a unique and short-lived fashion for funerary duels between two violinists had grown up in France: the soon to be deceased would leave a fragment of melody with his will, and two Funerary Violinists would improvise in turn upon the theme, at the interment, each attempting to conjure more tragedy from it than his opponent – the winner being the artist who drew the most tears from the assembled crowd. Although initially disgusted by the notion of competitive funerary performances, Sudbury found the imagination and sincerity of the players, particularly Dubuisson, most compelling, as he reveals in his Considerations:

Imagine my surprise at seeing the Duel advertised on billboards all over Paris, together with bold caricatures of the players, and an offer of wine, bread and cheese. Poor Couthon seemed hardly remembered in the spectacle of his own funeral……We assembled in the mid afternoon, once the service itself was concluded, and gathered at the graveside. Many rows of chairs were laid out for the spectators, and, behind them, there was a long table serving refreshments as promised, including bread, cheese and snails in garlic butter, together with a choice of fine regional wines. Immediately the performers arrived the hubbub turned to a murmur, and then to an expectant silence. Ladies stood fanning themselves affectedly, and gentlemen removed their hats. After a brief moment spent tuning their violins they took their positions, with Dubuisson at the head of the grave, and Couret at the foot. With deep solemnity, worthy of a Funerary Violinist, they intoned the sombre melody in perfect unison, then paused, bowed formally to each other, and the duel began.

Couret, who it turned out was the challenger, took the first variation, playing through the melody with the simplest of subtle ornaments, and pouring forth pathos and maudlin earnestness with an ever-widening vibrato that would have seemed uncouth in any other context. Slowing considerably towards the close of this, his first statement, he dwelt upon the cadence with a particularly fierce frown, and, upon arriving at its close, concluded with a florid bow to the audience that seemed more than a little out of place, but draw much applause nonetheless.

Throughout this time Dubuisson had stood, stock still as cemetery furniture, emanating the quiet dignity one would expect from an acknowledged master, in the face of a childish challenge. Finally, once the applause had died away, he raised his bow to the violin and opened with a single preparatory note so deeply wreathed in sombre woe that it would have melted the heart of even the coolest of politicians or executioners. Then, ever so slowly, he solemnly intoned the notes of the tune, dry as the bones beneath his feet, in the perfect conjuration of the hollow barrenness of mortality, making us all feel aghast at the emptiness of our own lives; before introducing, with the subtlety of a wily cleric, the smallest glimpse of hope amidst tragedy and peace amidst despair, through the clever and most emotional use of the upside down mordant. Finally, before closing this, his first statement, he took the simple melody and somehow, as if in a dream, turned it on its head, revealing how the soul will rise and, just for a moment, we glimpsed the very gates of heaven itself. As he lifted his bow from the strings there was a shocked and utter silence from the assembled crowd, and it must have been nearly a minute before we could shake ourselves from the heavenly images he had so presented, and erupt into rapturous cheers and applause. At this point I felt great pity for poor Couret, the poor pretender, who was so obviously out of his league, and yet duty bound to continue……

This description continues, in similar vain, for many pages, detailing the general tone and techniques applied by the performers, in often poetical and melodramatic terms. Finally, after four more statements from each of the players, he describes the conclusion of the dual:

…… and as he [Dubuisson] drew to a close, slowly leading us down into the very deepest depths of unremitting misery, I was momentarily distracted by the gentle sound of sobbing from an elegantly dressed young lady to my right, and, removed from the profound reverie he had so masterfully induced, I looked around and saw that each and every feminine countenance present was streaked with quiet tears, and every gentleman, his head bowed in an exaggeration of despair, was locked in the most profoundly tragic and mournful of contemplations. It was immediately clear that the duel was over, and as Dubuisson lifted his bow from the string for the final time, Couret, a pale and exhausted imitation of his former self, merely bowed to his opponent and vanquisher, and then turned his back upon us, walking off brusquely between the many tombs, not even taking the time to replace his violin in its box (this was attended to by his servant who followed behind him like a nervous puppy). Dubuisson then acknowledged his victory with a noble nod of his head, packed up his own violin, and then purposely strode away, with an air of might and dignity I have only ever seen before in an English Lord.

This entirely abhorrent and misjudged spectacle, which served no obvious spiritual nor memorial purpose, would have been no better than any music hall entertainment were it not for the unquestionable genius of Dubuisson himself, who held within his heart and hands the power to speak directly to both the Spirit and to God himself. Never have I heard such true notes played, such profound communication with both the dead and the living, entirely free from the dual sins of egoism and vanity so often present in the funerary arts. At that moment I knew that the future would bring us together both as colleagues and friends, and that, in some way, we were fated to lift the art of Funerary Violin out of its stagnant and corrupted tarn of vice, and raise it up to the true and sacred heights to which it once so naturally ascended…..

Quite what he meant by its stagnant and corrupted tarn of vice is uncertain, although it is clear that Sudbury enjoyed a melodramatic style of writing, and it may be no more than an affectation to emphasise the heights of which he dreamed. (There is no evidence of corruption amongst Funerary Violinists of this period, and the Chiswick scandals of the 1790s (in which additional obligatory costs were added to the Violinists fee for the hire of a violin, bow, and black ribbons) had been firmly dealt with by the Guild at the time.) The impression Dubuisson made on him was to be borne out by a sudden change in his own pieces, which expanded their vision, for the first time, beyond simple marches, and the works of Herr Gratchenfleiss, to include a whole vision of a sacred rite. Four years later, when Dubuisson travelled to England, they were to work together in formalising the Funerary Suite to free it from the ever-present potential for indulgence and moral decay.

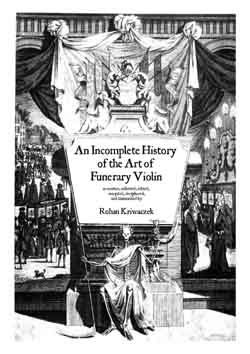

extracts:

- Read the Forword

- Read an extract from the Introduction

- Read Wilhelm Kleinbach - the Last of the Practicing Funerary Violin

- Read the Funerary Violinist Today

To purchase a copy signed by Rohan Kriwaczek, author and Acting President of the Guild of Funerary Violinists, and stamped with the official Guild of Funerary Violinists stamp for only £24, plus £1 postage worldwide, click below

|