foreword

I have often been asked how I came to be involved with the Guild of Funerary Violinists, and, indeed, it is an interesting tale, to me at least. On completing my advanced diploma at the Royal Academy of Music with considerable honours in the early 1970s, my mind was filled with delusional dreams of becoming a concert soloist. Having done little other than play the violin since the age of seven, my unbounded naivety left me completely blind to the many eternal realities of the life of even the greatest of musicians, and for a number of years I floundered on the shoreline of popular success, endlessly surprised by the astonishing ignorance (as I saw it then) of the critics and audiences alike. But, alas, the fantastical determination and vigour of youth is soon worn out, and I was reluctantly forced to embrace the actuality of my existence. Looking around me at the few colleagues and friends who had found a niche in the many-cornered industry of Classical music, I saw that specialisation was the key to a successful career. Some colleagues were playing exclusively 17th century music on period instruments, some only played modernist chamber music, one had moved from the violin to the musical saw, and one had a flourishing career in the more theatrical end of the industry, playing the works of J.S.Bach backwards (with some most musical results) though it must be admitted that after a brief television appearance his success was short-lived. What was needed, in the cynical seventies, was a gimmick, though I insisted on finding a gimmick with some degree of artistic integrity.

I had always been drawn to the more tragic and solemn works, indeed I believe that is what drew me to the violin in the first place – it’s inherent, deeply felt tragedy of tone – and so I resolved that henceforth I would only play the saddest of music, indeed I would market my concerts as The Saddest Music in the World. I vigorously delved into the libraries and archives of all of London’s music college seeking ever sadder works and by May 1975 I had assembled a fine repertoire of profoundly sonorous pieces and had embarked upon a tour of Northumberland (I chose Northumberland both because of its distance from London – I was admittedly a little nervous of the critical response of the London scene – and because of the likelihood of a great storm blowing up during my concerts, a notion which I felt would add to the sense of gloom and tragedy I was there to impart). It was after one of these concerts that I was approached by a rather tall and stiff looking gentleman, previously unknown to me, who invited me to attend a meeting of the Guild of Funerary Violinists. He was, it turned out, an amateur musician from London, who was in Northumberland to take the air due to a chronic case of nocardiosis (a debilitating lung disease caught by inhaling particles of earth), and a member of the board of the Guild, and, though I have promised not to mention his name, nor that of any members of the Guild since Herbert Stanley Littlejohn (who died in 1957), I will be forever grateful to him, as this introduction was to change the course of my life and vocation forever.

My initial impression of the Guild was not terribly inspiring, indeed a more dreary collection of fellows could not be imagined, by me at least, although Dickens did at times come close. After a couple of meetings, where we discussed the Funerary Aesthetic, and the terrible events that befell the Guild, I was almost ready to leave for good, but then mention was made of the Guild’s archives. Immediately my interest was rekindled, and I asked, nay begged, to be given access to whatever materials they may contain. It took a couple of months for me to gain their trust but finally I was allowed to see the archives first hand.

Never in the history of record keeping has there been a more chaotic, disorganised or neglected archive as this. The conditions were atrociously damp, pages were rotting, trunks were falling apart on top of each other, objects were stacked with all the cognizance of a landslide, and I realised, at that moment, that it was my mission to preserve, collate and study whatever was not beyond saving.

It did not take long before their initial suspicion of my motives turned to enthusiasm and even, at times, assistance, but the task itself is painstakingly slow. Much of the material amounts to little more than clues and fragments, and many years of earnest restoration and scholarship were necessary for even the simplest of stories to slowly reveal their full form.

In 1982, mainly due to my devoted research into their history, I was elected Acting Secretary of the Guild, and, it must be admitted, used my position, in part, to nominate many new members, and slowly eliminate the paranoid old guard, whose deep conservatism had only served to further condemn the Guild to isolation and ignominy. It was in this way that I was able to drag what had become little more than a stuffy gentleman’s club for amateur musicians into the 21st century.

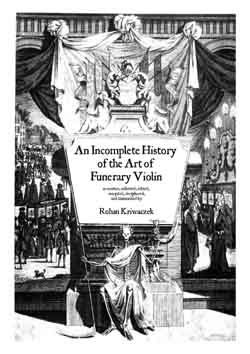

Although never a Secret Society, the persecution it had received during the 19th century, combined with indifference throughout the 20th century, had caused the Guild of Funerary Violinists to become a deeply secretive organisation over the years. When I first mentioned, in 1980, that some of these works should be available in the public domain, the reaction I received could be described as outright horror. It took until the year 2002 for the composition of the board to have changed substantially enough for a provisional permission to be given for me to compile a book, and accompanying collection of CDs and sheet music, and even now there are many prohibitions: mainly that I must mention very little of the Guild’s history beyond 1841, and nothing whatever after 1914 – with a few notable exceptions that have been specifically agreed.

The history of the Art of Funerary Violin is deeply fragmentary, being made up of little more than glimpses, rumours, and occasional pieces of evidence that were missed by the agents of the Vatican during the Great Funerary Purges of the 1830s and 40s. Since I embarked on this enterprise of discovery and consolidation many new documents have come to light, some due to my own efforts, some discovered independently, some of which had been in the vaults of museums and libraries all along, either incorrectly catalogued, or simply never studied until now. Given this lack of sequential evidence the story I am attempting to portray could be vastly altered at any time by some new discovery or conclusion. I am limited to reporting those few facts evidenced by materials I have seen for myself, representing the many rumours and insinuations that abound around the history of Funerary Violin, and making occasional speculations on my own part.

My intention behind compiling this book is to bring the venerable art of Funerary Violin once again out into the open space of public consciousness. It is a history defined by the evolution of Art, Politics and changing attitudes to Mortality, which holds many lessons for us all. Like a great tree, whose roots reach all the way back to the renaissance of modern man, it has born many fruits over the years; some that mouldered where they fell, some that sprouted shoots of their own, and some that were picked and carried many miles away to feed the souls of other musics in far distant lands. In the last 30 years, a number of such works have come to light, after years of idle obscurity, and may now be brought to the attention of scholars and musicians alike. That these pieces, born of Man’s courageous struggle with his most ancient of all enemies, should be heard once again in their true context, is undeniable by any who claim to value Art and Spirit above the tedium of everyday existence. I therefore offer up these pages, the humble fruits of many years of painstaking scholarship and research, that History might once again be rewritten, and perhaps, some day in the future, churchyards and cemeteries all across Europe, might ring to the sonorously cathartic tones of the solo Funerary Violinist.

Rohan Kriwaczek B.A.hons M.Mus F.G.F.V.

Acting President

The Guild of Funerary Violinists.

extracts:

- Read an extract from the Introduction

- Read Charles Sudbury's account of a Funerary Duel

- Read Wilhelm Kleinbach - the Last of the Practicing Funerary Violin

- Read the Funerary Violinist Today

To purchase a copy signed by Rohan Kriwaczek, author and Acting President of the Guild of Funerary Violinists, and stamped with the official Guild of Funerary Violinists stamp for only £24, plus £1 postage worldwide, click below

|