Programme Notes: The current revival of Klezmer music is, at least in part, based on a nostalgia for a world long gone; a world dominated by poverty, repression and a fundamental insecurity. Our shtetl dwelling ancestors would probably be horrified by our current romanticisation of a life that they were often desperate to escape. My own Jewish ancestors had moved out of the Pale of Settlement by the middle of the nineteenth century, into Austria, becoming Viennese, and my father can recall the often ferocious anger that would ensue if he accidentally used a Yiddish word or phrase. I myself, when busking, playing Jewish violin music, have been accused of dragging all Jews back to the shtetl, by elderly Jewish women in Hove.

On the other hand, in this society, that is ever more concerned with the notion of roots, and ethnicity, it is no surprise that the Yiddish speaking culture, actively destroyed by Israel’s adoption of Hebrew as a national language, is now being revived by those born into the comforts of the new world. As a Jewish violinist I am as guilty as the next man, and in writing this piece I am, in a sense, further romanticising the past.

This conflict was one of the elements that I intended to explore in the piece – trying to marry my own love of traditional music, with a sense of the danger and naivety involved: danger – because romanticising a genuinely desperate lifestyle is always dangerous; naïve – because the music itself expresses a simple world of traditional dances and social order that is long passed.

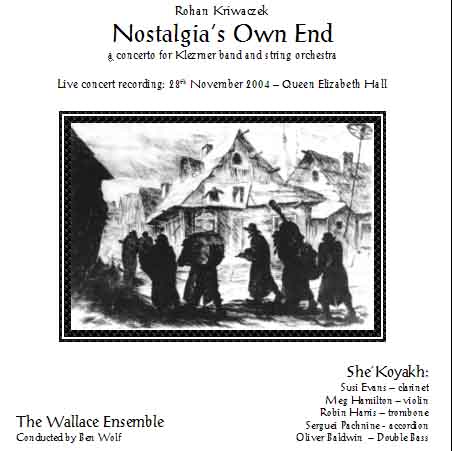

The piece falls roughly into four linked movements. In the first, the general argument ensues; the Klezmer band repeatedly strike up simple tunes which the orchestra first colours in and then attempts to undermine, as if to say “things can’t be that simple any more”. Towards the end of this movement the argument between the two gets more intense and aggressive.

The second movement features the clarinet and violin as soloists, and is the only part of the piece that quotes from the Klezmer archive – based on a doina (a slow, ornamented introductory melody) taught to me by Deborah Strauss, and taught to her by Michael Alpert who learnt it from Leon Schwartz; the only Klezmer violinist to pass on his skills first hand to a member of the current generation of klezmorim. This movement draws to a close with a simple melody on the trombone, which is then taken up by the strings.

In the third movement the Klezmer band repeated attempts to strike up with an irritating little tune, but on each occasion the orchestra interrupts and tries to take it somewhere more serious. Sometimes the band joins in, sometimes they fight, and the movement concludes with the two forces screaming trills at each other.

The final movement is a short funeral march, started by the orchestra, which the band mistake for a march of triumph. They are led like lambs to embrace their tragic fate.

As a final word I must add that in my experience the creator of a work of art is rarely the best judge of what they have made, and is often completely deluded as to the result of their labours. What I have written here is what I intended. What you hear may be completely different. A word of advice – trust your own judgment more than mine. |